Tal como fué aprobada, la Declaración de Virginia fue principalmente debida al trabajo de George Mason; el cómite y la Convención hicieron algunos cambios gramaticales y añadieron los Arts. X y XIV. Esta declaración sirvió de modelo para las equivalentes en las constituciones de diversos estados y fué una fuente de la Declaración de Derechos del Hombre y el Ciudadano en Francia, aunque el grado de influencia sobre documentos posteriores es una cuestión muy controvertida. La referencia a «propiedad» en el Art. I puede compararse con el uso de esta palabra por Locke, su omisión por Thomas Jefferson en el segundo párrafo de la Declaración de Independencia, y su uso en las enmiendas V y XIV de la Constitución estadounidense.

Declaración de derechos hecha por los representantes del buen pueblo de Virginia, reunidos en convención plena y libre, como derechos que pertenecen a ellos y a su posteridad como base y fundamento de su Gobierno

- Que todos los hombre son por naturaleza igualmente libres e independientes y tienen ciertos derechos inherentes, de los cuales, cuando entran a formar parte de la sociedad, no pueden, mediante contrato alguno, desposeer o despojar a la posteridad; a saber, el disfrute de la vida y la libertad, con los medios para adquirir y poseer propiedad, y la busqueda y obtención de la felicidad y la seguridad.

- Que todo poder reside en el pueblo, y, en consecuencia, deriva de él; que los magistrados son sus administradores y sirvientes, en todo momento responsables ante el pueblo.

- Que el gobierno es, o debiera ser, instituido para el bien común, la protección y seguridad del pueblo, nación o comunidad; de todos los modos y formas de gobierno, el mejor es el capaz de producir el máximo grado de felicidad y seguridad, y es el más eficazmente protegido contra el peligro de la mala administración; y que cuando cualquier gobierno sea considerado inadecuado, o contrario a estos propósitos, una mayoría de la comunidad tiene el derecho indudable, inalienable e irrevocable de reformarlo, alterarlo o abolirlo, de la manera que más satisfaga el bien común.

- Que ningún hombre, o conjunto de hombres, tienen derecho a emolumentos diferentes o exclusivos, o privilegios de la comunidad, sino en consideración a servicios públicos, los cuales, no siendo hereditarios, implica que tampoco han de serlo los cargos de magistrado, legislador o juez.

- Que los poderes legislativo y ejecutivo del estado deben ser separados y distintos del judicial; que a los miembros de los dos primeros les sea evitado el ejercicio de la opresión haciendoles sentir y participar en las cargas del pueblo; para ello deberán, en períodos fijados, ser reducidos a su situación privada, devueltos a ese cuerpo del que originalmente fueron sacados; y que las vacantes se cubran por medio de elecciones frecuentes, fijas y periódicas, en las cuales, todos, o alguna parte de los anteriores miembros, sean de nuevo elegibles, o inelegibles, según dicten las leyes.

- Que las elecciones de los miembros que servirán como representantes del pueblo en asamblea, deben ser libres; que todos los hombres que tengan suficiente evidencia de un permanente interés común y vinculación con la comunidad, tengan derecho al sufragio, y no se les puede imponer cargas fiscales a sus propiedades ni desposeerles de esas propiedades, para destinarlas a uso público, sin su propio consentimiento, o el de sus representantes así elegidos, ni estar obligados por ninguna ley que ellos, de la misma manera, no hayan aprobado en aras del bien común.

- Que todo poder de suspender leyes, o la ejecución de las leyes, por cualesquiera autoridad, sin consentimiento de los representantes del pueblo, es injurioso para sus derechos, y no se debe ejercer.

- Que en todo juicio capital o criminal, un hombre tiene derecho a exigir la causa y naturaleza de la acusación, a ser confrontado con los acusadores y testigos, a solicitar pruebas a su favor, y a un juicio rápido por un jurado imparcial de su vecindad, sin cuyo consentimiento unánime, no puede ser declarado culpable; ni tampoco se le puede obligar a presentar pruebas contra sí mismo; que ningún hombre sea privado de su libertad, salvo por la ley de la tierra o el juicio de sus pares.

- Que no se requieran fianzas excesivas, ni se impongan multas excesivas; ni se inflinjan castigos crueles o extraordinarios.

- Que las ordenes judiciales generales, por medio de las cuales un funcionario o agente puede allanar un lugar sospechoso sin prueba de hecho cometido, o arrestar a cualquier persona o personas no mencionadas, o cuyo delito no esté específicamente descrito o apoyado en evidencia, son opresivas y crueles, y no deben ser extendidas.

- Que en controversias sobre la propiedad, y en conflictos entre hombre y hombre, es preferible el antiguo juicio con jurado a cualquier otro, y debe considerarse sagrado.

- Que la libertad de prensa es uno de los grandes baluartes de la libertad, y que jamás puede restringirse salvo por un gobierno despótico.

- Que una milicia bien regulada, compuesta del cuerpo del pueblo entrenado para las armas, es la defensa apropiada, natural y segura de un estado libre; que en tiempos de paz, los ejércitos permanentes deben evitarse por peligrosos para la libertad; y que en todos los casos, los militares deben subordinarse estrictamente al poder civil, y ser gobernados por el mismo.

- Que el pueblo tiene derecho a un gobierno uniforme; y, en consecuencia, no se debe nombrar o establecer ningún gobierno separado o independiente del gobierno de Virginia, dentro de sus límites.

- Que ningún gobierno libre, o las bendiciones de la libertad, pueden ser conservados por ningún pueblo, sino con una firme adhesión a la justicia, moderación, templanza, frugalidad y virtud, y con una frecuente vuelta a los principios fundamentales.

- Que la religión, o las obligaciones que tenemos con nuestro Creador, y la manera de cumplirlas, sólo pueden estar dirigidas por la razón y la convicción, no por la fuerza o la violencia; y, por tanto, todos los hombres tienen idéntico derecho al libre ejercicio de la religión, según los dictados de su conciencia; y que es deber mutuo de todos el practicar la indulgencia, el amor y la caridad cristianas.

Aprobada por unimidad el 12 de junio de 1776

Convención de los Representantes de Virginia

Borrador redactado por el Sr. George Mason

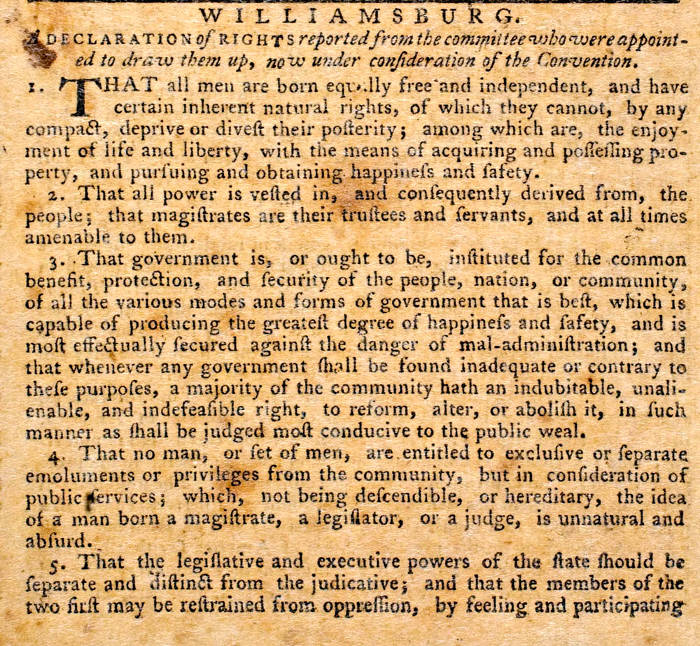

A declaration of rights made by the representatives of the good people of Virginia, assembled in full and free convention; which rights do pertain to them and their posterity, as the basis and foundation of government.

- That all men are by nature equally free and independent, and have certain inherent rights, of which, when they enter into a state of society, they cannot, by any compact, deprive or divest their posterity; namely, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.

- That all power is vested in, and consequently derived from, the people; that magistrates are their trustees and servants, and at all times amenable to them.

- That government is, or ought to be, instituted for the common benefit, protection, and security of the people, nation or community; of all the various modes and forms of government that is best, which is capable of producing the greatest degree of happiness and safety and is most effectually secured against the danger of maladministration; and that, whenever any government shall be found inadequate or contrary to these purposes, a majority of the community hath an indubitable, unalienable, and indefeasible right to reform, alter or abolish it, in such manner as shall be judged most conducive to the public weal.

- That no man, or set of men, are entitled to exclusive or separate emoluments or privileges from the community, but in consideration of public services; which, not being descendible, neither ought the offices of magistrate, legislator, or judge be hereditary.

- That the legislative and executive powers of the state should be separate and distinct from the judicative; and, that the members of the two first may be restrained from oppression by feeling and participating the burthens of the people, they should, at fixed periods, be reduced to a private station, return into that body from which they were originally taken, and the vacancies be supplied by frequent, certain, and regular elections in which all, or any part of the former members, to be again eligible, or ineligible, as the laws shall direct.

- That elections of members to serve as representatives of the people in assembly ought to be free; and that all men, having sufficient evidence of permanent common interest with, and attachment to, the community have the right of suffrage and cannot be taxed or deprived of their property for public uses without their own consent or that of their representatives so elected, nor bound by any law to which they have not, in like manner, assented, for the public good.

- That all power of suspending laws, or the execution of laws, by any authority without consent of the representatives of the people is injurious to their rights and ought not to be exercised.

- That in all capital or criminal prosecutions a man hath a right to demand the cause and nature of his accusation to be confronted with the accusers and witnesses, to call for evidence in his favor, and to a speedy trial by an impartial jury of his vicinage, without whose unanimous consent he cannot be found guilty, nor can he be compelled to give evidence against himself; that no man be deprived of his liberty except by the law of the land or the judgement of his peers.

- That excessive bail ought not to be required, nor excessive fines imposed; nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.

- That general warrants, whereby any officer or messenger may be commanded to search suspected places without evidence of a fact committed, or to seize any person or persons not named, or whose offense is not particularly described and supported by evidence, are grievous and oppressive and ought not to be granted.

- That in controversies respecting property and in suits between man and man, the ancient trial by jury is preferable to any other and ought to be held sacred.

- That the freedom of the press is one of the greatest bulwarks of liberty and can never be restrained but by despotic governments.

- That a well regulated militia, composed of the body of the people, trained to arms, is the proper, natural, and safe defense of a free state; that standing armies, in time of peace, should be avoided as dangerous to liberty; and that, in all cases, the military should be under strict subordination to, and be governed by, the civil power.

- That the people have a right to uniform government; and therefore, that no government separate from, or independent of, the government of Virginia, ought to be erected or established within the limits thereof.

- That no free government, or the blessings of liberty, can be preserved to any people but by a firm adherence to justice, moderation, temperance, frugality, and virtue and by frequent recurrence to fundamental principles.

- That religion, or the duty which we owe to our Creator and the manner of discharging it, can be directed by reason and conviction, not by force or violence; and therefore, all men are equally entitled to the free exercise of religion, according to the dictates of conscience; and that it is the mutual duty of all to practice Christian forbearance, love, and charity towards each other.

Adopted unanimously June 12, 1776

Virginia Convention of Delegates

Drafted by Mr. George Mason